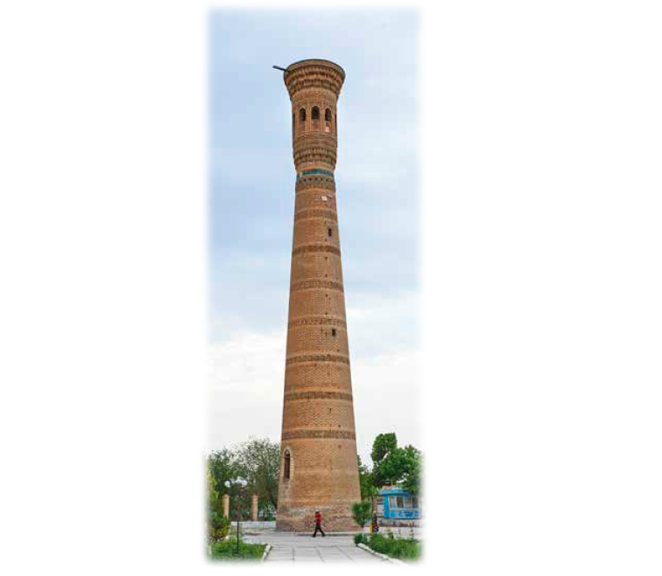

Given the technical complexity of the construction of minarets, they were erected mainly at large mosques. Researchers of medieval Muslim architecture note that of all the components of the mosque, it was the minarets that most fully reflected the stylistic features of local schools of cult architecture: «...the architectural appearance of the mosque, uniform for the Muslim world, did not take shape, and could not, because everywhere it was closely connected with local construction and artistic traditions. The architecture of minarets is even more indicative in this respect» (Brittanitsky A. S. 1960. p. 40). Minarets were usually erected near large mosques and served to call believers to prayer. But at the same time they served as a landmark, a kind of beacon for caravans and travelers, as well as a watchtower and a signal tower. The early Islamic minarets have not been preserved, perhaps, following the example of the first burnt-out minaret of Bukhara, they were built of wood or, like the above-mentioned minaret in Pikend, of raw. Natural factors (a seismically active region) adversely affecting the structures of tower construction. They were built in the traditional local form; round in cross-section, with thinning trunks, minarets were completed with a light superstructure in the form of a lantern-rotunda. In the Islamic world, minarets first appeared under the Umayyads in Syria. Over many centuries, various types of them have been formed: square (Iraq and Iran), spi-ral (Iraq and Egypt), cylindrical or round barrelled (Iran and Central Asia). An unusual type of tower in the form of a corrugated decorative trunk on a faceted polygonal base is a 12th -century minaret from Jarkurgan of Surkhandarya region, which has analogies in Northern India and Khorasan. However, this type has not received further distribution in the territory of Uzbekistan. As mentioned above, the first minaret was built in Bukhara back in 919 and has not been preserved. The most famous is considered to be the Bukhara Kalyan minaret of the beginning of the 12th century, which can be considered as an architectural prototype of most minarets on the territory of Uzbekistan. Over time, throughout the Islamic world, minarets ceased to be used as a place of call to prayer and acquired the character of a plastically expressive architectural decoration. This was partly due to technical reasons — the height of the minarets and the difficulty of regularly lifting the azancha, which called the faithful to prayer, up the internal spiral staircase. Since the middle of the 20 century in Iran, the proclamation of the azan was carried out from the height of the entrance portal, and minarets, as a rule, are they were used only as decoration on both sides of the portal and did not have a guldast — a turret for the azancha. The number of minarets at one mosque in the historical cities of Central Asia was small — one or two. As a rule, a pair of minarets were built on the sides of the high portal of mosques. The trunk of the minarets consists of an outer wall of an annular section and an inner column for the entire height of the minaret. Inside the trunk, a brick staircase spiraling around the pillar leads to the upper platform, simultaneously connecting the pillar and the wall. The conical shape of the trunk, which gives an elegant harmony to the mina-rets, lowered the center of gravity of the structure and thereby increased its stability under wind load and earthquakes. Earthquake resistance was also given to the structure by a special alabaster mortar, the plasticity of which allows the structure to deform to a certain extent and not collapse instead of severe resistance. Among the construction techniques that increase the stability of minarets is the laying of stone slabs and wooden beams in their cross section. The minaret in Dzharkurgan is the only minaret in Central Asian architec-ture with a corrugated surface. A small village sprawled around the monument is called «Minor village» — a village with a minaret. The base of the minaret is a high octagonal plinth, each face of which is decorated with a shallow arched niche. Rectangular frames with inscriptions made of hewn terracotta slabs are placed above the decorative niches. In one of the sides of the plinth there is a narrow arched entrance leading to a spiral staircase in the trunk of the minaret. A slender telominaret placed on a plinth consists of sixteen semicircular columns tapering to the top forming a corrugated surface. In Bukhara, during the period when it became the capital of the Karakhanid state, a cathedral mosque was built with the Kalyan minaret, which communicated with the mosque building by a bridge from the roof of its courtyard gallery. The mosque has not survived to our time. The powerful trunk of the minaret with a height of 45.6 m with a lower diam-eter of 9 m dominates the city superstructures. Continuously following the height of the trunk one after another belts of flat and relief masonry represent an example of magnificent ornamental art of the 12th century. The inscription on one of the belts contains the name of Arslan Khan and the date of construction – 1127. The minaret, which has stood for almost nine centuries without repair, belongs to the outstanding works of engineering art. The Kalyan minaret is similar in shape and ornamentation, but slightly lower than it (38.7 m) and slimmer is the minaret erected in 1196–1197 in the small village of Vabkent in the Bukhara oasis.