In the 13th century, first the peoples of Maverannahr, and then other countries of the Islamic world, experienced a historical collapse caused by the devastating invasion of the hordes of Genghis Khan. The first global clash of two civilizations - steppe paganism in the form of the Mongolian Yasa and Islamic monotheism was aggravated by another, no less dramatic collision — the clash of the culture of the steppe and the city. There were clashes with nomadic, steppe dynasties in the history of the Islamic caliphate, but they were carried out by fellow believers and did not have such a total and most often senseless destructive effect.

The consequences of the invasion had a detrimental effect on the economy, trade, political and spiritual life of the peoples of the Caliphate, putting an end to this largely nominal, but systemic religious and political structure. The brutal assassination of the last caliph Al-Mustasim in 1258 by the grandson of Genghis Khan Hulagu led to the death of the true Caliphate. On the territory of Iran and Iraq, Hulagu founded his dynasty and received the title of Ilkhan (Khan of a part of the country) from his brother, the Great Khan Kublai.

Despite the fact that his cousin, Khan Berke, who, unlike Hulagu, converted to Islam, expressed indignation and, as revenge for a fellow believer, declared war on his fellow tribesman and relative, in fact, the causes of clashes between the two Mongolian clans were not related to the Islamic factor, but with the struggle for territories between the Golden Horde and the country of the Ilkhanids, the founder of which was Hulagu.

As we can see, in the Mongol empire divided into several uluses, the khans who ruled them - the descendants of Genghis Khan — adhered to various religious beliefs. Most adhered to the Mongolian nomadic charter — yases, some khans, for one reason or another, converted to Islam.

Maverannahr, as a state nominally subordinate to the caliphate, lost its former status due to its fall. By the will of the new conquerors — the Chingizids of the Chagatai branch, a state was to be created on the territory of Maverannahr, subject to the Mongol rulers. The sharp anti-Islamic position of Chagatai, a zealous supporter of the Mongolian yas, the adherence of the first rulers of the Mongols to nomadic traditions and antipathy towards urban civilization were the reasons that hampered the development of Muslim architecture in Maverannahr.

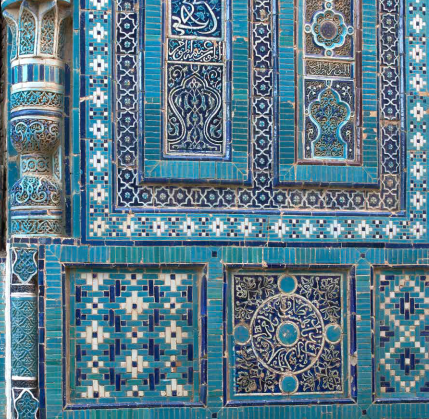

In the middle of the 13th - the middle of the 14th centuries in the architecture and crafts of Maverannhar, the process of restoration was slow and not as large-scale as in Ilkhanid Iran. Its peculiarity was associated with historical circumstances — the indifferent attitude of the new authorities in the person of the Chagatai khans to the development of cities, the weakening of the role of Islam in Maverannahr, the lack of strong state administration on the part of the proteges of the Mongol khans. There is no imperial ambition in architecture; there are no monumental majestic buildings in this period. This was the period of a kind of proto-Temurid style, the manifestations of which were not so bright and powerful, but nevertheless, to a certain extent, paved the way for the formation of the actual Temurid style of architecture and arts.

Over time, part of the Mongol khans, who settled in the territory of Maverannakhr, under the pressure of circumstances, began to convert to Islam, but they practically did not contribute to the development of urban planning and the construction of mosques or madrasahs.

Against this unfavorable historical background, the reign of Amir Temur and the Temurids looks like a phenomenal phenomenon, when the flourishing of the economy and culture on the territory of Maverannahr led to the creation of unsurpassed masterpieces of architecture and crafts of world significance. Researchers of the history of architecture single out the period of the mid –13th – 70s of the 14 th century as the initial stage of the restoration of «cities and the revival of the activities of local architectural schools», while the next stage – the 70s of the 14th century and the continuation of the entire 15th century characterized as the rise of cultural life, reminiscent of the Renaissance in the West (Rempel. 1961, p. 256).

HISTORY OF THE ARTS OF UZBEKISTAN Akbar Khakimov